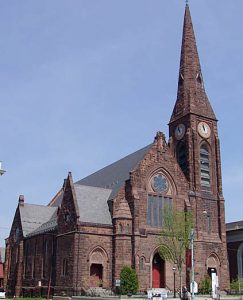

A few years ago, I went to Northampton, Massachusetts. My naive hope was to see the spot where Jonathan Edwards preached the Word of God into so many hearts during the First Great Awakening. There’s a small rock with a few words about Edwards. There’s a fifth church, rebuilt in 1877, which stands on the same hallowed ground. My surprise wasn’t the minimal recognition or even the newer building. It was the moral choices made by the First Baptist Church and First United Church of Christ who share the historic property and call themselves the First Churches. There’s a reason for my surprise, as you might well know, due to the convicted life of Jonathan Edwards.

Powerful Preachers from the Past: Jonathan Edwards

Northampton Church (today)

Jonathan Edwards (1703-1758) is a prominent historical figure from the 1730s and 40s for several reasons. First, his journal, letters, books and sermons help shape what we know of the times and continue to be influential. Second, his connection with the fiery and animated George Whitfield (and, indirectly the Wesleys) certainly compliment Edwards as a figure larger than the 1,100 souls who lived in Northampton. Third, his diehard want for conversion leaves a mark, then and now. Edwards didn’t want passive members who only surrendered their time, but not their hearts and minds, to Jesus. He didn’t want any half-way covenant, as it was called (and accepted) during that time in New England. Formally, the Halfway Covenant was put in place by Edwards’ grandfather and mentor, Solomon Stoddard (1643-1729). It granted full access to church membership by the children of believing parents, and, here’s the catch: even if the children did not hold to Christianity or otherwise participate in church life. It became a slippery slope which brought little conviction of sin or renewal to the congregation. Edwards knew it.

Northampton Church (1730s)

Edwards began his pastorate in Northampton in 1726. He had returned from Yale, the young college founded in part over the growing concerns of theological liberalism at Harvard, and wanted to begin a thoughtful ministry. His ministry would be based in the words that God showed him in I Timothy 1:17 as a student: “Now to the King eternal, immortal, invisible, the only God, be honor and glory forever and ever.” That he would even become a pastor may seem an odd decision due to his philosophical and scientific interests, being inspired by both John Locke and Isaac Newton, among others. But Edwards would use his studies in ministry, framing for his congregation a God who masterfully designed the world and invites them into conversion and faithful obedience. In 1727, he married Sarah Pierpont whom he had met in New Haven some years earlier. They would go on to have 10 children.

Revival seems more than an apt word to define what began to occur 1734. That Sunday in November, he began a sermon series under the subject, “We are justified only by faith in Christ, and not by any manner of goodness of our own”, taken from Romans 4:5. If you’ve ever read Jonathan Edwards, you know his sermons methodically trod through the defense of doctrine ways of application. Everything is linked back and defended by Scripture. Nothing is loosely spoken or brought together in colorful anecdotes. In short, when we read Edwards, we might wonder how The Great Awakening began… here… in such uncharismatic hands… in 1734. Nevertheless, the Holy Spirit came and by the spring, there were 30 conversions happening each week. God was using Edwards to do the mighty work of revival:

Certainly in the hearty embracing of a Savior from the punishment of our sinfulness, there is the exercise of a sense that we are sinful. We cannot heartily embrace Christ as a Savior from the punishment of that which we are not sensible we are guilty of. There is also in the same act, a sense of our desert of the threatened punishment. We cannot heartily embrace Christ as a Savior from that which we are not sensible that we have deserved. For if we are not sensible that we have deserved the punishment, we shall not be sensible that we have any need of a Savior from it, or, at least, shall not be convinced but that God who offers the Savior, unjustly makes him needful, and we cannot heartily embrace such an offer. And further, there is implied in a hearty embracing Christ as a Savior from punishment, not only a conviction of conscience, that we have deserved the punishment, such as the devils and damned have, but there is a hearty acknowledgment of it, with the submission of the soul, so as with the accord of the heart, to own that God might be just in the punishment. – (November, 1734)

The spirit of awakening continued for the following decade, after the, “great work of God that was wrought here”, as Edwards says. “There has remained a more general seriousness and decency in attending the public worship,” he says. “There has been a very great alteration among the youth of the town with respect to reveling, frolicking, profane and unclean conversation, and lewd songs. Instances of fornication have been very rare. There has also been a great alteration among both old and young with respect to tavern haunting. I suppose the town has been in no measure so free of vice in these respects for any long time together for this sixty years as it has been this nine years past.”

In October of 1740, after much anticipation by both men, Jonathan Edwards and the tent revivalist George Whitefield finally met. Unlike the bookish, ordered pulpit delivery of Edwards, Whitefield was a firebrand, itinerant preacher who delivered at least 18,000 sermons to perhaps 10 million hearers. In Northampton, Whitefield preached four times with a message, “suitable to the circumstances of the town,” Edwards says, “containing just reproofs of our backslidings, and, in a most moving and affecting manner, making use of our great profession and great mercies as arguments with us to return to God, from whom we had departed.”

In those years, God was working in many places – in Pennsylvania with the preaching ministry of William and Gilbert Tennent, in Virginia with Samuel Davies, and throughout England with John and Charles Wesley, to name a few. The reverberations are still felt today, especially in the strong legacy of sound doctrine being a mighty conduit for God to speak into people’s hearts.

Edwards wouldn’t retire as the emeritus pastor of his church. In 1750, the congregation kicked him out because he attempted to rid it of all Halfway Covenant remnants and call the people to more holy lives. He moved to the borders of Massachusetts, became a missionary pastor to 150 Mahican and Mohawk families, and continued to write. In 1757, he became president of the College of New Jersey (today Princeton University) and died a few months later.

So, back to my trip to Northampton. I’d imagine if a reenactment of Edwards’s “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God” were performed, the sermon’s final plea would be responded to with a shallow ripple of smug chuckles. “Therefore, let every one that is out of Christ, now awake and fly from the wrath to come,” Edwards preaches, “The wrath of Almighty God is now undoubtedly hanging over a great part of this congregation. Let every one fly out of Sodom: ‘Haste and escape for your lives, look not behind you, escape to the mountain, lest you be consumed.'”

What can we do as pastors, knowing our moment in history is so much more within a fallen world? Here are a few lessons I see in Jonathan Edwards. I hope they’re helpful.

Substance over show

Let’s concentrate on the substance of the sermons from our pulpits and not so much the messenger. Historians suggest that Edwards read his sermons with little gesture and inflection in his voice which might help balance where we concentrate our preparation – less on delivery and more on doctrine.

No halfway measures

This is a difficult one because there is so little support in people’s daily lives to push them toward holiness. Edwards took a stand that would not only cost him his pulpit, but would shrink the church if enacted. It is easy for us to want the requirements of holiness to be lessened or amended. It may show up through our minimal membership requirements or absence of church discipline or simply our reluctance toward confrontation. Luke 20:18 says, “Everyone who falls on that stone will be broken to pieces; anyone on whom it falls will be crushed”. Let us be broken.

Compassion and truth

Edwards was not without compassion. The message of God’s invitation is throughout his sermons and it’s a compassionate plea to be converted and join the people of God. However, it’s a truthful message. It doesn’t hide Hell in a corner for some other, more suitable time to discuss. “O sinner!” Edwards preaches. “Consider the fearful danger you are in: it is a great furnace of wrath, a wide and bottomless pit, full of the fire of wrath, that you are held over in the hand of that God, whose wrath is provoked and incensed as much against you, as against many of the damned in hell. You hang by a slender thread, with the flames of divine wrath flashing about it, and ready every moment to singe it, and burn it asunder…”

Jonathan Edwards is a powerful preacher from the past, and one who can speak into our present ministries as we are carried along in the Gospel work God calls us to do. If you want more resources on Jonathan Edwards, I’d encourage you to visit edwards.yale.edu.